If you “train clients” in the fitness profession, chances are that you call yourself a trainer.

I say the phrase “train clients” loosely enough to encompass anyone in the fitness industry who works with clients towards some fitness goal.

But if you are like most forward-thinking fitness professionals, especially the ones who play in the online space, you shouldn’t call yourself a trainer. Moving away from the trainer/trainee mindset might be the most powerful thing that you can do.

The Trainer, The Coach, and the Designer

What we call a “trainer” is really one of three roles: a trainer, a coach, or a designer. Let’s look at what distinguishes these roles from one another.

The Trainer

The defining characteristic of a “trainer” is the assumption that the trainer’s client will follow orders.

In other words, the client is expected to live in the trainer’s reality, where the trainer has complete control. The trainer directs the client with the complete, utter, unflappable assumption that those instructions will be executed.

Of course any fitness professional worth a dime is spilling their whey in a hissy fit about the fact that – similar to Lyle McDonald’s friends – this only exists in an imaginary world.

But in specific contexts, there are times when client adherence isn’t an issue. Think about fitness professionals who work with clients on the gym floor. During the hour-or-so session that they’re together, that person is a trainer.

One of the implications about not worrying about adherence is that recommendations can be physiologically optimal. Getting a hypothetical 3% extra return in MPS by perfecting a client’s post workout timing or carb-to-protein ratio makes sense.

But what if we can’t assume complete adherence? What happens if you introduce the notion that clients can choose not to obey you. This is where psychology comes into play.

The Coach

When you can’t assume complete adherence, you cross over into the “coach” realm. The distinguishing characteristic from trainers is that coaches have to deal with a client’s psychology.

Coaches have to deal with the fact that clients won’t always do what they say. Even worse, you might not even know if a client isn’t adhering; the client might be smiling and nodding at your recommendations while mentally telling you to fuck off.

This means that a good coach can no longer optimize for the physiologically optimal. Good coaches need to understand things like the limitations of your client’s willpower, the countdown to client activation, disrupting binge eating thought patterns, or why your clients obsess over the scale like a cat with a laser pointer.

So all you have to do is motivate your client to follow your plan? Simple right?

Not quite. It turns out people aren’t easily motivated. Even worse, the act of attempting to motivate them may push them the other way entirely. I write more extensively about this here.

After a while, many coach/client relationships turn into a tug-of-war over whose version of reality is correct.

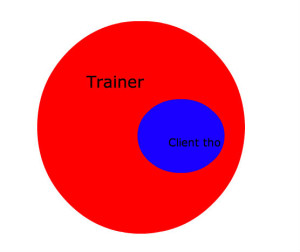

Let’s use some concrete examples to explain the images above.

The client above didn’t hit her macros, because she was stressed with work, didn’t feel like her macros are attainable, and ultimately felt frustrated with her coach.

Her coach thinks that she’s simply making excuses.

“She could have hit her macros if she really wanted. I don’t understand why she’s even upset with me. She’s paying me to coach her.”

As a coach you will absolutely encounter the scenario above. The temptation will be to tell her to jump off a cliff or join the nearest CrossFit box. (Same thing, right?)

I’ve been there. It’s much easier to write this off as a hopeless client. But if you do the hard thing and understand that this is a very naturally occurring phenomenon, you can turn the situation around.

In order to do that, however, you have to become a designer.

The Designer

In the example above, the client and the coach are “wrestling” over the client’s recommendations.

As explained in Motivational Interviewing, a successful relationship between you and the client needs to look more like dancing, not wrestling.

Fitness designers are different from coaches in that they take into account the client’s environmental factors. By adopting this paradigm, you can elevate yourself to the most powerful of roles and become a “fitness designer.”

Designers takes it one step further than coaches by utilizing their knowledge of motivation, habit design, and nutrition. They then work with the client to describe an objective reality and use this reality to make decisions.

Let’s use a real client story to see how this works.

I have a client (let’s call her K) who typically trains after work. K is typically splendid, but she hasn’t been able to motivate herself to go to the gym lately.

The first thing that I wonder is why her motivation is low. She says that work stresses her and seems to depletes her of mental energy. I see if she can train in the mornings, but her schedule makes this impossible.

After digging around more, I then discovered that she was going home before the gym and the temptation to get off the couch was too much. She was going from a high-stress environment to a low-stress, relaxing environment, making it hard to leave the house afterwards.

Knowing BJ Fogg’s research on changing small habits and knowing how the habit loop works, we worked together to find a solution, which ended up being simple:

Change into gym clothes at the end of work, before going home.

As a designer, you can describe a shared reality that both you and your client agree with, and then figure out the best course of action.

Wearing Different Hats

Notice the thought process at the two different ends of the spectrum.

The trainer is concerned about the physiologically optimal. The perfect squat form and whatnot. The client is in the trainer’s world, and the trainer could care less about the client’s life.

The designer is concerned with the client’s habits, environment, and thought patterns. Understanding these requires knowing as much as you can about your client’s life.

These three roles aren’t mutually exclusive. You’ll need to switch between all three, just like you might need to switch between being a parent, a boss, etc.

One role isn’t necessarily better than the other. It depends on context. For example, Dr. Layne Norton is one of the fitness experts in the world. Because he focuses on making champion bodybuilders, he will most likely be in coach mode.

But if you, like most fitness professionals reading this, are hoping to change the lives of Average Joe and Average Jane, the best thing that you can stop doing is thinking of yourself as a trainer. (Again, this doesn’t apply to all folks, such as those whose clients have strength or physique goals, but it does apply to those who want to reach the masses.)

Once you have a good understanding of evidence-based fitness (this should be a prerequisite) you’ll become a better coach if you spend your time elsewhere. The material that makes the most powerful of these hats isn’t made from fitness. It’s made from empathy.

One thing that I’ve noticed is that the best coaches aren’t just the fitness-obsessed. They appreciate philosophy, art, culture, music, as much as they appreciate science. This is no coincidence; designing around your client’s life means relating to it as much as possible. These are things that you must learn outside of PubMed or the gym.

In reality, you’ll probably still call yourself a trainer. Or a coach. That’s totally fine. It’s the paradigm shift, not the label, that’s important.

Although please don’t ever say “I’m a fitness designer,” because that would just make you a tool.

p.s. If you’re interested in online coaching, make sure to sign up to be a Fitocracy Team Fitness coach where you can connect with a platform of 2-million users.

Comments are closed.