I only really excel at a handful of things (aside from drinking) so I don’t brag much. But I’m going to brag for a bit for the sake of an important concept.

Between my personal group and one-on-one coaching, I believe that I have one of the highest client transformation success rates out there. Keep in mind that all of my clients are your “Average Joe,” most of whom could never get into fitness consistently. I’m literally inundated with client messages saying “this is the first program that has ever worked for me.”

Now, I wasn’t always a good coach. My methods once consisted of handing out macros and then yelling at clients when they missed their targets. This worked for fitness enthusiasts, but the second that I started training “normals,” nine out of ten trainees dropped off. Compare this to my current Fitocracy Team Fitness training group, in which I retained 39 out of 40 trainees month-over-month, standard deviations above the norm.

It’s worth noting that I have no fitness credentials. None. Nada. Zip. You might think that my client success rate is despite this, but I believe that it’s actually because of this.

Here’s why this is important.

My degree is in economics/business with a concentration in Operations and Information Management. After college, I cut my chops on advertising research (fun fact, I co-authored the first whitepaper on ad retargeting), growth metrics, and lots fun quantitative things around spreadsheets. (Which allows me to legitimately say “Hey girl, did you know I model for a living?”)

It’s precisely this lens, and not the traditional fitness lens, in which I view the world that gives me a unique perspective. In particular, the utilization of data and metrics gives me a leg up as a coach.

Don’t worry. I’m going to share this with you. But first…

What the hell do tech metrics have to do with fitness?

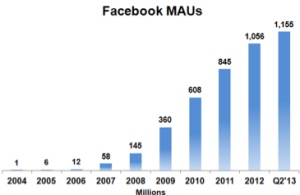

The short of it is that tech people are nerds. They track a lot of data, then model and optimize relevant metrics, such as retention or monetization. This exercise is incredibly powerful. Facebook, for example, has been able to grow like gangbusters because they determined the levers that keep people active on the site.

Basically, this allows tech people to play “Moneyball” with its users. They figure out what factors make people stick around or open their wallet, then they go and optimize these factors as much as they can. Just like in Moneyball, decisions are numerically-based, and they remove guessing and romanticism from the picture.

Can we, as coaches, apply some of these concepts in order to reduce client churn and increase satisfaction? You bet.

A Primer on Activation

In tech, user behavior can be modeled using Dave McClure’s AARRR model (not to be confused with Alan Aragon Research Review).

At the top of the funnel, you have acquisition. These are all of the people that register for a product or service.

At the top of the funnel, you have acquisition. These are all of the people that register for a product or service.

Just because someone registers, it doesn’t mean that they automatically become an active user. For that to occur, that user must experience “activation,” the next part of the funnel. We’re going to focus on this part of the funnel for the rest of this article.

A user becomes “activated” when he or she experiences the product or service’s magic “aha” moment. If a user never has this critical experience, they will eventually churn, i.e. never use the app again.

Each product has a unique definition for “activation.” For example, Facebook realized that the definition of activation was “having a user add 7 friends in 10 days.” Facebook will actually mold your entire initial experience around getting you to activate, even to the point of annoyance. Why? Because nothing else matters if a user does not activate.

This point is so critical that it’s worth restating.

Facebook is willing to risk annoying the living shit out of you, because if you don’t activate, you aren’t going to stick around. For that reason, they are willing to take that tradeoff. After you activate, Facebook stops being so pushy and lets you continue as normal.

It’s obviously paid off. Facebook has grown faster than a 15-year old on creatine.

Let’s look at some other products and their definition for activation.

MailChimp allows users to curate email lists, create campaigns, and send emails. Sure, curating lists and designing emails are great features, but the user likely doesn’t experience the “magic moment” until the first campaign is successfully sent. Therefore, sending out a campaign is MailChimp’s definition of “activation.”

One more example. Sometimes activation requires a bit more work. Let’s take a look at OkCupid. (Yeah I’m always losing my keys.)

The point of a dating site is to match two people together. For that reason, activation probably occurs when there is a mutual match someone has their first message exchange. You can probably guess that OkCupid sends more eyeballs to newer users who have not yet activated. (I may or may not have just revealed a secret protip of mine.)

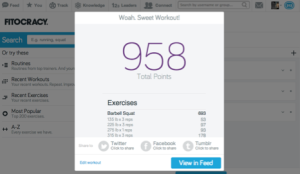

A Case Study – Fitocracy’s Activation

Fitocracy’s definition of activation wasn’t immediately obvious to us, because the site has a ton of different uses; you can do everything from track a workout to browsing pictures of cats.

When we dove into the numbers, however, we found that all retained users had one thing in common – they all logged a workout. That makes sense. You’ll probably never discover any of Fitocracy’s other features until you get your feet wet by tracking something.

Once we realized this, we went to work in order to increase activation. We reduced the number of screens between registration and the “track” page, A/B tested a lot of copy in order to get a user to track, and sent emails and notifications reminding users to track a workout. We eventually increased activation by 40%

The result? 30 day retention increased side-by-side as well.

Cool story, bro. What does this have to do with fitness?

Remember, activation isn’t a metric that’s only applicable to products. It’s also a metric that’s applicable to services, such as training. The only difference is that the client’s use case (their goals, starting point, persona, etc.) determines the definition of activation.

Let’s look at an example. What do you think activation is for someone who wants to lose weight? Let’s call this client “Computer Joe.”

If you guessed “see the number on the scale go down” you are correct, although there are a few interesting things to note here.

First off, as experienced coaches probably already know, the goal of weight loss may be veiled under a statement like “I just want to be healthier.” Some clients find it embarrassing to explicitly state their interest in weight loss, so you’ll have to read between the lines. Don’t be fooled – a decrease in scale weight is still this client’s definition of activation.

Secondly, I explicitly chose the term “lose weight” rather than “lose fat.” Sadly, scale weight is such a hardwired metric that these clients won’t be satisfied simply with reducing their waist measurements. (Yes, this is usually true no matter how hard you try to explain that they’re “simultaneously building muscle” when waist decreases and weight goes up or stays the same.)

Ok, so we’ve established that in a client like Computer Joe’s case, the definition of activation is “seeing his scale weight go down.”

If that’s true…

What the FUCK is this shit??

… or this shit?

Because these are the types of things that I see recommended to clients whose main goal is weight loss.

Right. I know that lots of these recommendations are important. Corrective exercises, mobility, cardio, stretching, taking your vitamins, fish oil, etc., are all important. In fact, there are an infinite amount of recommendations that, in isolation, could increase a client’s health and fitness.

But the most important point stands:

Unless a client is activated NOTHING else fucking matters.

That means that all friction needs to be reduced en route to activation. You can always add additional recommendations later. Sure, they might be things that seem “healthy,” or “good for their fitness,” but they really aren’t, because they decrease the client’s long term fitness success. (Have I mentioned how much I hate the word “healthy?”)

Computer Joe is only one particular use case. Obviously, different client use cases will have different definitions of activation. A “hardgainer,” for example, will probably be “activated” once the scale shows an increase or they hit a PR on a major lift.

Now, you can’t manage what you don’t measure, so it’s important to track activation with your clients.

I track clients by start date and note when that client is activated. It’s important to keep in mind when a client’s start date is, because unless activation occurs, you’re going to lose that client. The amount of time that a client will stick around without activation obviously depends on the client, but anecdotally, I’ve found that range is somewhere between 3-6 weeks. And that takes a lot of managing expectations, explaining what’s going on, etc.

A Case Study – Casey

Let’s take a look at Casey (whose name definitely wasn’t derived from “Case Study” because I’m writing this super late at night… or should I say early in the morning).

Casey is female, 5’1, 190, untrained, estimates that she’s 35% bodyfat, and is unable to lose weight. From all the different types of weight loss clients I’ve had, she’s actually the most difficult in the world to activate. (I write more about this here.)

Hey, if we can activate her, we can activate anyone right?

Casey claims that she’s unable to lose weight even at 1,100 calories/day. That seems incredibly low. As with most women who seem to be infinitely stalled, the first thing that I do is ask her if she binges on eating and/or cardio. She says yes to both.

At this point I think “hmmm, perhaps she’s possibly consuming 1,100 calories/day on most days, then binging puts her at caloric maintenance?”

The next thing that I do is calculate her caloric maintenance. I’m a fan of using the Katch-McArdle formula for RMR (because it incorporates lean mass), then applying a relatively medium activity multiplier (1.4). Doing this, it looks like her maintenance calories are 2,200. Is that right? From experience with clients like her, that seems a bit high.

Perhaps her body fat approximation is off. Let’s see. If we assume her estimation is correct, that puts her lean mass at 2.0 lb/inch. From past client data, I know that’s in line with an intermediate male, whereas untrained women are typically closer to 1.5 lb/inch. That means she’s somewhere closer to the 50-55% range and her maintenance calories are closer to 1900-2000/day.

At this point, I put her on a mild caloric deficit (~300 kcal/day), set her protein at 140g (typically the most that women can eat when starting out), increase her carbs to the maximum amount that still keeps fat intake reasonable, and recommend a strength training regimen.

Then, we wait.

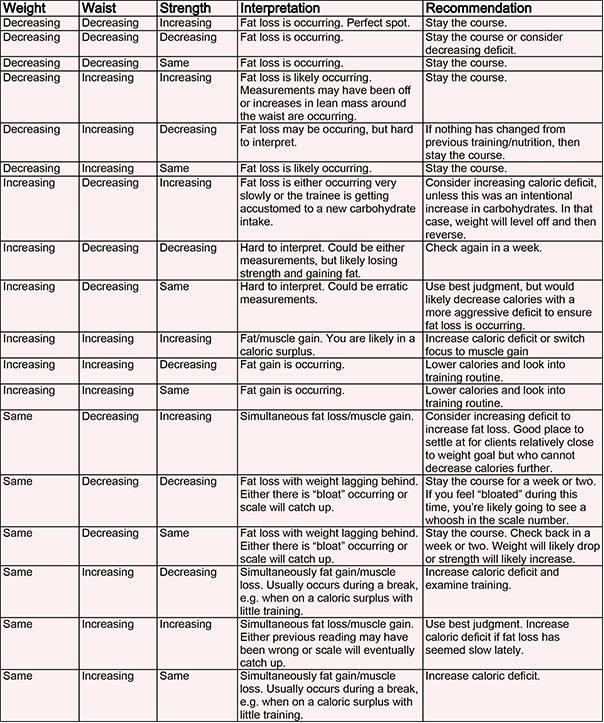

In clients like Casey, women in the 40%+ body fat range, I almost always see the same pattern. After a few weeks, as predicted, Casey’s weight either stays the same or increases, while her waist measurements decrease linearly. (I have a few guesses as to why this pattern exists, but that’s for another post.)

I assure Casey that fat loss is occurring, but I can tell that she’s getting restless and frustrated. In the meantime, we go over assignments in order to increase her mindfulness and self-compassion, two skills that will help her combat binge eating.

At the four-week mark, I start to get antsy, because I know that Casey is going to churn if she doesn’t activate soon. Casey has lost two inches off her waist, but is still sitting at 190.5. She emails me that she’s about to cave in, and I keep reassuring her.

Then, just like magic, she wakes up one day at 187. She is activated and weight loss is relatively linear week-over-week from there. I’ve seen this pattern in overweight women with eerie frequency. Here is weight data (in kilograms) from an actual client that shows the typical weight pattern.

Know what’s the best part about activation? The amount of client trust greatly increases. Casey, has yoyo dieted, binged, and had a broken relationship with food for as long as she can remember. She’s now finally free from that cycle. Any client resistance disappears and she becomes loyal to you for life.

That’s the great part about activation. Clients are naturally skeptical when your recommendations are different from what they’ve heard – and most of what they’ve heard is wrong. Activating them creates a form of trust, and from there you can add additional recommendations to their program.